memcpy_s

Friday, May 22nd, 2009On Friday, an article ran on Slashdot making note that Microsoft is “banning” the C function memcpy in favor of the new memcpy_s. While memcpy_s has in truth been around for a while, the notion that it would now generate compiler warnings has created quite an uproar. Some people seem curious as to why so many people are upset by what seems a pretty innocuous change. The article author asked if was going to affect anyone’s creativity. I can assure you that’s not the concern.

In a nutshell: the problem is you can’t tape a cupholder to a formula one race car and declare it street legal. It still doesn’t have any bumpers, it’s too low to be safe around other cars, and if you aren’t an expert driver you still shouldn’t be driving it. A cupholder doesn’t change that.

So what? A cupholder is still an improvement… right? Who doesn’t want a cupholder? Imagine for a moment that having the cupholder suddenly disqualified you from a number of races. You couldn’t run that race if you have a cupholder. It also slowed down your car–not a lot, but a tiny fraction of a second. Maybe it doesn’t slow it down enough to matter, but in those few races won by hundredths… well, maybe it does. Suddenly that cupholder doesn’t seem so nice.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting giving up on attempts to improve memory management and prevent buffer overruns. I just question if this exact approach was the best one.

Memcpy_s is basically a race car with a cupholder. While memcpy_s will certainly prevent some bugs, the same people who got one parameter wrong are just as likely to get two parameters wrong… and cause all new bugs in the process. Garbage In = Garbage Out. It doesn’t matter what the calling convention is.

On two occasions I have been asked,—”Pray, Mr. Babbage, if you put into the machine wrong figures, will the right answers come out?” … I am not able rightly to apprehend the kind of confusion of ideas that could provoke such a question.”

— Charles Babbage, 1864

discussing the first mechanical computer

The change also comes with a price: it breaks cross-compatibility with other compilers, including older compilers on the same operating system as well as other platforms. This means the same code can’t cross-compile anymore if you use memcpy_s. Someone with Microsoft suggested that GCC should pick up the change as well. Perhaps, but that assumes that GCC is the only other compiler that matters. Certainly, it’s the most popular other compiler that matters, but it’s far from the only one especially if you do embedded systems work or anything running on “exotic” hardware. And let’s be honest–if you’re not writing something that’s fast or exotic, you’re probably not writing it in C. The exception, of course, being legacy code… but surely that’s even less likely to be changed. The whole point of legacy code is that you don’t have the time\budget to update it, otherwise you wouldn’t be running it at all. These are the guys who will wrap memcpy_s in a macro named memcpy, defeating it entirely. Sigh.

As for that speed difference I mentioned? We’re obviously only talking about an extra comparison operator and perhaps a branch or two here. I know an extra comparison operator seems trivial, but if an extra comparison operator didn’t matter ASSERT macros wouldn’t exist. The speed difference is nominal, but it’s very, very real. On a lark I timed it. Copying 32 bytes 100,000 times with memcpy took on average 3952 counts, or about 0.001104 seconds, measured to nanosecond accuracy with QueryPerformanceCounter. Performing the identical operation with memcpy_s took on average 9706 counts, or about 0.002712 seconds. This was in “release mode” using Visual Studio 2008. (For the curious, in debug mode the difference averaged 8028 counts to 11340 counts, but you shouldn’t be shipping your code in debug mode anyway!)

Now hopefully you’ve done everything you can to avoid memcpy in your inner loop in the first place, but we all know there are rare occasions where it’s unavoidable. This all brings me back to my earlier point: if you’re not writing something that’s fast or exotic, you’re probably not writing it in C. Yes, you can write your own memcpy that’s probably faster than the system memcpy if you’re really worried about speed, but now we’re back to the portability issue. In short, I’m certain that to the people where the choice of language matters, those few clock cycles matter too. We’re talking folks writing device drivers here, not business applications.

Nobody is twisting anyone’s arm to use memcpy_s. You can easily disable the compiler warnings and continue to use memcpy all you like. But hopefully you see where I’m going with this: A lot of the reason that people continue to use C for certain projects has to do with performance and portability. This change sacrifices both for dubious return. If the change is not going to have tangible benefits that outweigh the problems, why do it at all?

Sooner or later, you need to trust that the programmer knows what they are doing. If the programmer can’t manage memory responsibly, you’ve got a bigger problem than an extra parameter is going to fix. To be honest, while a lot of people don’t like to admit it programmers sometimes leak or botch memory even in managed languages. There’s certainly a thesis paper or two in “possible alternatives” to the approach taken–perhaps checking the block size by querying the allocator instead of asking the programmer which would be even slower but more reliable, borrowing ideas from double entry accounting, etc, etc.–although the “real” fix surely involves more intelligent ways of thinking about memory, which realistically means a fundamental change in constructs, not a patched function.

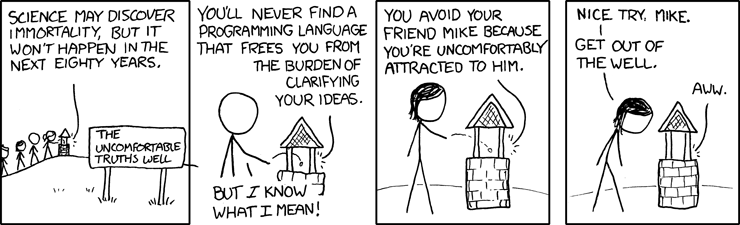

As always, XKCD sums it up best (panel #2):

Ah, I wait for the day… 🙂